LA CHANSON D'ASPREMONT

MODERN FRENCH BY LOUIS BRANDIN, 1925

FROM A POEM OF THE 13th CENTURY

ILLUSTRATIONS BY M.A. SERVANT

ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY NOL DREK

PART ONE: THE BATTLE AGAINST AUMONT

CHAPTER 1 - CHARLEMAGNE IN HIS PALACE IN AIX LA CHAPELLE

LORDS, would you like to hear how in Aspremont Charlemagne

defeated Aumont and Agolant who had come to give battle to the

army of the Christians, and how he dubbed Roland a knight and

girded him on his left side with Durendal? Listen to me: I begin

my song.

It is Pentecost. Charlemagne is in his palace at Aachen.

From all parts his men came to celebrate the anniversary of his

coronation. They crowd around him on the marble steps.

To gentlemen of high nobility Charles distributes fabrics

and coats of Alexandrian silk, good goblets, cups of fine gold, fine

goshawks, expensive hawks; to the poor knights he gives palfreys,

horses, and deniers.

"Lords," said Duke Naimon, "the crown must be placed on

the head of him who in power comes immediately after God. Now

listen carefully to these words: to all those of Germany, Apulia,

Romagna, Lombardy, France, Brittany, and Aquitaine, Charlemagne

forbids being bold enough to gird a sword at the side of a squire.

Let all those who wish to receive the strike on the neck come to his

court; Charles wishes to reserve the right to arm them as knights."

The king is filled with rejoicing and no one leaves him

without beaming with joy. Two kings and Naimon kneel before

him. "Sire," they declare, "those knights you see leaning against

the columns of the palace or lying on those silken cloths, there

is no land under heaven they are not ready to conquer for you. If

ever again any part of your empire is threatened, you can count

on their help; at your first call they will march against your

enemies.

"Naimon," said the Emperor, "truly, if the Saracens provoke

us again, it is I who will fight them. I will defeat them myself, then

I will distribute their spoils among all my lords, for I want all my

lords to owe all of their property to me alone."

CHAPTER 2 - THE MESSAGE OF BALAN

The meal is ready, the tablecloths are laid, the wine is poured.

Seven hundred gentlemen, sons of counts and renowned princes,

all dressed in ermine and petit-gris, are preparing to sit down to

table, but the king has not yet taken his seat, he has not yet left

the marble steps.

Suddenly a knight appears. His blond hair is braided in

plaits which fall over his shoulders and down to his hips. His

large eyes shine brightly. His face breathes joy and gaiety. If the

ardent sun had not tanned him, his complexion would be as white

and as delicate as that of a virgin. He has sharply cut features,

large arms, and a strong chest. He stands tall. He has a slender leg

and a well-turned foot. When he enters the palace, his only

clothing is his bliaud which falls in two sections on his sides. He

withdraws his sword with a chiseled gold hilt and passes it to a

Turcopole who is behind him.

Right glove in hand, he approaches the emperor and says

to him in a loud and firm voice, so as to make himself heard, "May

Mahomet, our God, who watches over us, protect Agolant and

Aumont, Trïamodés and Gorhant, and all their armies, and strike

down proud Charles and all his advisers! Yes, Charles, your

unworthy conduct towards my lord has filled him with just wrath.

For more than a month Agolant has been riding through your

lands and ravaging your kingdoms. He wants to strip you of it to

punish you for your bad deeds. And I who have been sent to you

as a messenger, you see this ring that I have on my finger? To be

able to keep it, I have sworn out of love to the one who gave it to

me, and who is far from being ugly, to kill a Frank with my own

sword."

"Friend," said Charles smiling, "may God have mercy on

us!"

"Sir Emperor, listen to me. There are three vast lands in

the world, the names of which I can tell you. One is called Asia,

the second Europe, and the third Africa. There are no others.

These three lands are separated by the sea. It is of the best of the

three that my sire is master. Last year the pagans consulted fate

and it declared that the first two should be united with Africa.

Well then, my lord comes to seize your Europe. All that is left for

you, Emperor, is to make a deal with Agolant. As for me, my name

is Balan. I serve as ambassador to the king. I have not been

accustomed to speaking lies or vain words, if you demand proof

of what I put forward here, I am ready to give it to one of your

vassals. If you do not listen to my advice, you will act like a fool.

You have no army that can tame ours, we will seek you until we

find you, nothing will save you, neither the woods, nor the earth,

nor the sea, unless you can fly like a bird. And now, if you dare,

designate the best of your men to take up my challenge and take

this message. If you find a word that goes beyond what I told you,

reserve for me the ignoble fate of the thief caught in the act."

At these words, he throws the letter on the Emperor's

mantle. The latter gives it to abbot Fromer. The abbot breaks off

the wax, he sighs, cries with both eyes, spreads his fingers and

drops the parchment.

Archbishop Turpin picks it up. "Sir Emperor, you are

wrong to give your messages to such people as can read them.

Formerly, in his youth, Fromer found consolation only in wine. He

is good to promise, but not to give. Do you know why he cries

now? It is because he sees himself obliged to empty his treasury for

others. Go, sir abbot, go and sing your matins, go and recite the

life of Saint Omer. As for me, I am going to read Agolant's letter."

Abbot Fromer responds violently, but Charlemagne cries out,

"Let the messenger speak!"

Standing, the Archbishop then speaks in a loud and firm

voice. "Here is Agolant's message: There are three lands in the

world. I am master of the largest. After crossing the African Sea, I

have arrived in Calabria. I left neither wife nor child there. I

swear by Mahomet and by Tervagant that, if you do not renounce

your faith in God, if you do not bow your head under our law, if

you do not become a follower of our religion, then your life will

not be worth one bezant."

The French say: "Truly, Agolant speaks well and knows

how to use threats very well."

Turpin resumes, "Here is what Agolant says again: I,

Agolant, have a great red heart against you, Charlemagne. I will

destroy Christianity, with my two hands I will kill you and

Aumont, my son, will be crowned in Rome. I come with all my

army which numbers seven hundred thousand men. Before you

can reach the plains of Romagna, Christendom will be brought to

a pitiful state. If, however, I decide not to put you to the edge of

my burnished sword, you will never campaign again. At the very

most I will give you a land to govern of which you will be

seneschal. I have spoken."

And Balan asks the great emperor, "What shall I reply to

Agolant, my lord? You certainly do not dream of fighting him any

more than the mallard would think of fighting the goshawk.

There are a hundred thousand men who form our vanguard and

it is I who must strike the first blow, it is a right that I hold from

my ancestors. I have a horse white as an apple blossom, on my

blue gonfanon are embroidered three lions with grimacing

mouths. When you see your people fighting against ours, you will

not be wise unless you are seized with fear. If you do not give up

this struggle, my two eyes will search in vain for a being subject

to a worse condition than yours."

At these words, the king wants to strike him. But Duke

Naimon hastened up. "Thank you, handsome sire, in the name of

God the Creator! Such an act, we would blame it on you."

Then Charlemagne exclaims, "He is lying, the pagan

traitor! Tell your lord that, in a few days from now, I will carry my

Oriflamme to Aspremont."

The night begins to fall. Charlemagne walks over to the

table. The messenger is about to leave. He wants to ask for

Charlemagne's leave but Duke Naimon takes Balan by the arm.

"Do not be in a hurry, messenger. Of those who come to speak to

the Emperor, none can return on the first day. Come to our feast. I

will show you three hundred horses. You will take the two best,

they will replace yours who are tired from running."

Balan hears him and looks at him from top to bottom.

"Foolish Christian, you want to tempt me. I am not here for

presents, but to carry out the mission entrusted to me by my

lord. If I could meet you in Aspremont, I would make you pay

dearly for your words."

"Sire," said Naimon, "for the moment let us leave this

subject."

To Balan they bring a mantle of petit-gris, lined with silk

from overseas. The Saracen wraps himself in it, gets up and goes

to the table. Naimon accompanies him to his place, opposite

Charlemagne. The Duke of Bavaria passes the golden ewer to

Balan and he pours it himself. Balan, with a worried brow,

lowered head, sees the hall full of lords, dressed in petit-gris, vair,

and ermine, and wearing bliauds of silk. He sees the cups of fine

gold and silver, coming from the treasury of Constantine that

Charlemagne conquered across the Rhine when he defeated the

Saxon Witikind, sparkle in the light of the twisted wax candles.

Balan eats and notices how much Charlemagne dominates the

whole court. He cannot take his gaze away from the emperor's

beard, which falls to his chest, and he says to himself, "If

Charlemagne had only those who are here drinking his perfumed

wines to serve him, that would be enough to tell me that Agolant

has undertaken a crazy thing. Charles believes only in God, in him

he places all his confidence and his hope."

Charlemagne calls him, "Messenger, brother, tell me what

King Agolant has in mind. Does he really want to destroy holy

Christianity?"

"Yes, Sire, he hates it. This summer he will conquer Apulia

and Sicily, and this winter his son will be crowned in Rome. He

will search for you until he finds you."

"Ah, God!" said Charlemagne, "Allow me to shatter these

plans. Brother, messenger, do not forget to tell your master that I

warn him not to come up against my forces in Apulia, if he ever

enters there."

"Agolant," replies Balan, "wants to possess everything that

Alexander conquered in his age, he claims it as sovereign. His

armies are mighty. There is no man who equals him in wisdom,

he wears a flowery beard on his chin, he hates you with an

implacable hatred. You do not dare fight him. Let us settle the

quarrel in single combat. If I defeat your champion, I will lead

you to Aspremont. You will join your hands before Agolant, you

will pay homage to him, and you will receive the gift of land."

"Brother," said Charles, "do you know what we will do?

You are going to leave, and we will stay here. This country is his

when we flee!"

The Emperor has finished eating; the golden ewers are

passed again and the tablecloths are removed. Duke Naimon

lodges the messenger Balan. There is no fruit or fine morsel that

he does not procure for him, and all night long they discuss

Mahomet and Our Lord.

The next morning, Balan said to Naimon, "I am leaving,

because I have been here too long. I will carry my message and I

will not delay doing what I have in mind."

Dawn appears, day begins to shine; Balan rides on the

handsomest of the two coursers that Duke Naimon has gifted

him. He leaves the town by the main road. Several times he turns

around. While riding, he thinks of Charles and his court. He

already regrets leaving the French where he found so much

kindness. Ah, if he were not afraid of being reviled by his family,

how he would hasten to ask for baptism!

CHAPTER 3 - BALAN ACCUSED BY THE PAGANS

Balan passes Apulia and Calabria and after three days of forced

riding here he is in Aspremont. He gets off his horse while Hector,

King Lampal's son, holds his stirrup. Through the crowd of

Saracens, he reaches Agolant whom he finds under a pine with

green needles.

"Have you seen Charles?" said the Saracen King. "And have

you spoken to him?"

"Yes, Sire, I did not hide anything from him. I saw him at

his annual coronation feast at Aix-la-Chapelle. By Mahomet,

Charles is brave, strong, and valiant, and his people prevail over

others as gold prevails over copper and other metals! He tells you

that in a few days he will come with his vassals to establish

themselves here. You can be sure, O king, that then there will be

terrible battles."

Trïamodés, the king of Valorie, furious, exclaims, "Cursed

be the messenger who so boasts of the enemy! If the proud

Charlemagne has given you his gold and his silver, you want too

much to show him your gratitude."

"Cursed be whoever dares to speak thus!" retorts Balan

sharply. "Yes, I saw Charles in his court at Aix. I threatened him

proudly, but I could not thereby fill him with fear. And Duke

Naimon gave me two horses to choose from among three hundred, the

slowest of which would still be considered very fast. I would be a

felon if I lied. By Mahomet, never have I seen people like

Charlemagne's! It seems that if one could socialize with the French

more often, life would gain in happiness and duration. And this is

what, for the sake of all of us, I have come without stopping to

tell you. However, no one here seems to want to take any account

of my words. If we fight, I will be the first to strike; it is a

right that I hold from my parents. Fie on the coward who dares not

face his peer! Besides, the future will show you whether I am

telling the truth or a lie."

King Moïsan, the one who bears the standard of Agolant,

rises and says, "Balan, tell us the truth and hide nothing from us.

Will Charlemagne deny his faith? Will he flee or will he wait for

us?"

Balan starts to laugh. "Fie on those who resort to lies! I

saw the messengers he was preparing to send. Certainly,

Charlemagne will come, be convinced of that. He has few people,

but they are full of valor. And now I am going to eat, for it has

been three days since I have taken any food."

Balan walks away. Then the pagan kings, king Moïsan,

king Danebus, king Hector, king Lampal the hoary, king

Trïamodés, and king Gorhant approach Agolant and they say

loud enough to be heard by him, "So Balan returned. In truth he

was bought by the French. All his words prove it. For our safety,

he must be drowned or hanged."

However, Balan has arrived at his house, where his people

give him an eager welcome. After having drunk and eaten well,

he prepares to set off again. He puts on silk stockings which

shape his legs, a silk jacket laminated with fine gold, a silk coat

edged with ermine and he jumps lightly on his shorn palfrey. He

returns to the courtyard where his enemies await, slandering

him. King Agolant is so irritated that he has almost lost his

senses. Balan is tall and strong, famous among all his peers for

his goodness. He appears among them like a falcon out among

the molting chicks. When he enters the great hall, all are silent

and remain mute. There is not one who does not wish him ill.

King Agolant speaks first. "Sir Balan, I cannot hide it. I fed

and raised you from your childhood and I girded you with the

sword on your left side. Your valor won you the royal crown. For

me you have taken pains and faced dangers. At the risk of your

life you went to Charlemagne in France. Now, you know that the

emperor holds a part of my heritage. That does not prevent you

from having told our great enemy everything about me and my

army in return for the presents that Naimon gave you. Now give

an account of your actions to your peers who will judge you. It is

life or death that is at stake for you at the moment."

Balan rises sharply and speaks in a loud and firm voice.

"Yes, rich King Agolant, you have nourished and raised me since

my childhood and on my left side you have girded me with a

sword. Finally, you gave me the crown of a king. But please tell

me, since I took up arms, is there one of your men who has

served you as much as I? Ever since I came from the Orient, I

have constantly won four battles for you. You have the land and I

have had great pains. Those around me who want to condemn

me to death make their conquests by staying at your side. Well,

let one of them rise and let him prove that the present of Duke

Naimon is the price of treason! Against all my accusers I offer you

my glove that I never committed the slightest villainy against you

at the court of Charles, and never allowed anyone to doubt my

faith in our gods, whatever I do in the future."

Salatiel, a noble and rich king, full of treachery, rises.

"Agolant, know this, that by his present conduct Balan has erased

all the services he could have rendered to you. His words have

filled your army with fear. They would have immediately fled

upon hearing him, if the sea had not been there to stop them."

Balan laments harshly, then he says, "Agolant, will you

believe King Salatiel, he who so often challenged you, he who one

day in the battle of the Vale of Timoriel slew ten thousand of your

men, him whom I brought back to your obedience, him from

whom I conquered thirty cities and as many castles? Will you

appeal to the testimony of the one who took your two nephews,

Durand and Ospiniel, the sons of King Cadiel, and who held them

in chains to finally kill them with his own knife?"

Trïamodés rises and says in a loud and firm voice, "Hear

me, Agolant. I think that the French have filled your King Balan

with dread. Well, give me France, I ask you. You will leave it to me

and you will return to Africa the great. However, by Mahomet and

by Tervagant, I will not be long in giving you the gift of Charles'

head! I will annihilate Saint Peter, whom Christians consider

their protector, before their very eyes, so that there will be no

one left to believe in paradise, and in its place we will put the

gods in whom we have faith. At Easter, I will have on my head the

crown of resplendent gold, then I will do you homage, and to

Balan I will deliver the justice that the man who believes in the

God of Christians deserves."

Balan hears him and in his heart he suffers from it. Full of

anger and bitterness, he said to the king, "Listen to me, Sir

Agolant. I repeat it to you, I who have served you for so long, I

repeat it to you and no one will make me deny it. I saw Charles

and his court. I heard his words and his threats. When you are

yourself in the presence of the French knights, covered with iron,

on their iron-clad horses, you will know what force you want to

fight against. Wait for that moment to judge if I have committed

an act of felony. If you then consider that I am a traitor, drive me

out of all the expanse of your country. But beware of Trïamodés

and his advice. I know why he hates me. Was it not I who

subjected him to your power and threw him at your feet? He will

never cherish me and, as the villain says in his proverb, 'The son

of the cat must take the mouse'."

Then Aumont, son of King Agolant, throws a look full of

fury at Trïamodés. He exclaims, "How is it that Trïamodés, the

king of Valorie, would like to prevail over me! As long as I am

alive and well, you will take France, you and yours, if you are

permitted. Seven years before this army was assembled, I was

given the land of the French. I will be the king! And if you judge

that we kill Balan, as one who deserves death, well, I assure you

we will not kill him. I am going to tell the truth, whether you

want to cry or laugh about it, whether you hate me or make fun

of me. Because of his value, his courage, his prowess, his brilliant

actions, Balan increased our power by seven kingdoms. There is

no king who can forget such services! No, I will not allow Balan

to be condemned to death!"

Aumont has spoken and all remain motionless. Then

Balan, boiling with anger, says, "Agolant, I am considered your

favorite and your strength, but you have caused me great

suffering on this day since you held me to be a traitor. There is no

man here, young or hoary, of high rank or of low origin, however

great his strength and his courage, that I will not hand to you

dead or vanquished, if he dares raise his shield against me."

Hector, son of Lampal, exclaims, "Shame on whoever

believes, as Balan says, that Charles would ever be daring enough

to do battle with you! Before he reaches us, we will have received

reinforcements galore. Seeing our great number, the Christian

army will flee in terror. And the villain said it, many years ago,

'Anyone who flees always finds someone to chase him away'."

Gorhant, son of Balan, stands up, irritated like a lion. All

undressed, he has a club in his hand, he is clothed in an ermine

cloak which hugs his body. Seneschal of the bold king Agolant,

warrior of the queen, who only loves him, he throws himself at

the knees of the king. "Agolant, this treason my father never

committed. I swear it and I wait here, sword in hand, that the

best of your men come and deny me."

Agolant does not breathe a word. Nobody moves, and thus

ends this quarrel between Balan's enemies and those that are

faithful to him, the bold sage who wanted so much to become a

Christian.

CHAPTER 4 - ARCHBISHOP TURPIN AT THE HOME OF GIRARD OF FRAITE

As soon as Balan leaves the court, Charles stops the feast. He

orders everyone to return to their country and prepare as quickly

as possible to fight against the danger that threatens Christianity.

Young and old alike obey, not without letting out sighs from their

hearts and tears from their eyes.

Our emperor is full of anger and fury. He has no desire to

laugh. "By the faith that I owe to Saint Mary," he exclaims, "to the

poor knights I will provide arms and wealth! For them I will

exhaust the treasures of my abbey down to the last penny, the

last cross, the last chalice." Charlemagne then appeals to all.

"Hurry up to accompany me on this pilgrimage. Against the

Saracens who want to despoil me of it, help me to maintain my

kingdom. They and their lineage will be banished forever! But, if I

keep my crown, I will give of my wealth to all. Let the Lombards

put on their armor immediately, for they will have to accompany

me." Our emperor is full of haste on this day. In great diligence he

returns to Paris. He immediately seals all his letters and sends

messengers to deliver them as soon as possible.

And Cahoer the rich king of the English, Gondebeuf the

noble king of Friesland, Burnols the good king of Hungary,

Salomon the valiant king of Brittany, Droon the valiant lord of

Mansois, Anseïs the powerful king of Germany, and David the

bold king of Cornwall each respond thus: "Tell Charlemagne that I

will come with ten thousand knights to defend him and to save

the Christian faith." And Desiderius, the illustrious king of the

Lombards, tells Charles that he will follow him to Rome with his

strong army, that he will provide him with food and will not

allow him to spend the cost of a clove of garlic for the

maintenance of his men.

And from all parts armies are marching towards Paris

with their kings, their dukes, and their princes, men of great

courage and high valor. However, there is still a lord who stands

aside. It is Girard of Fraite, the powerful Duke of Auvergne,

Burgundy, Gascony, Couzan and Gévaudan. He is related to

Archbishop Turpin. He is a baron full of pride, he holds neither

income nor fief from Charlemagne, and to the emperor he never

paid homage.

Charles with a proud face therefore calls Turpin, the

Archbishop of Reims. "Go find your relative, Girard of Fraite. Tell

him that, for the love of God, he must come to help me in the

fight for the salvation of Christianity! Afterwards I will repay him

for his support, if he ever needs my arm."

"I will go and find my relative," said Turpin. "He has four

sons who are bold knights, but I greatly fear this man full of

wrath and violence. On receiving your message, he may fly into a

rage and try to slay me in response."

"Sir Archbishop," replies King Charlemagne, "hasten with

your spurs and tell Girard to join me as soon as possible.

Moreover, passing through Laon, you will find in this town

Roland, Estolt, Haton, and Bérenger whom I raised in my house.

You will have them locked up in the keep of the castle. I want

them to stay there until the end of my battles against the

Saracens. They are too young to accompany us in our hard

campaigns."

"To the blessing of God!" replied Turpin. "All your orders

will be obeyed." Turpin leaves and first passes through Laon.

From Charlemagne he gives the order to keep the children in the

dungeon of the castle where they will have a cook and a wine

steward and a lot to eat and a lot to drink. The gatekeeper makes

a promise to Turpin and swears that he will not let them go out

in the evening or at night, and that he will forbid them to ride.

Then the noble archbishop goes in search of Girard. He

will not stop looking for him until he finds him. Without stopping,

he rides as far as Vienne, where he arrives on a day of fasting. He

waits until he is at the castle gate to pull on the reins of his horse.

"Friend gatekeeper," he said, "let me in now!"

"Withdraw," answers the gatekeeper. "Girard is busy

having dinner. I dare not allow anyone to pass. Tomorrow, you

will see him when he goes to the monastery."

"Gatekeeper," said Turpin, "I have charge of a message

which I cannot delay. Here, take these four golden bezants and

lower the bridge for me, and unlock the door for me."

And the gatekeeper replies, "In the name of Our Lord,

most willingly." The drawbridge is lowered, the gate unlocked,

and Archbishop Turpin ascends into the keep.

At table he finds Girard, the noble and proud duke. Many

knights dine with him and his four sons serve him. The

archbishop greets Girard, "May God, who created the sea and the

fish presented to you by your noble children, save and protect the

son of King Beuvon and may he bless him in the name of the

great King Charlemagne! Charlemagne sends you this message:

Agolant and Aumont have arrived on Christian land with an army

as large as we have ever seen. Beyond Aspremont they burn the

country. They massacre men, women, and children. Come with

Charlemagne to fight, be his companion in arms against the

Saracens. If you refuse, you will not be a sage and wise man."

Hearing these words, Girard changes color. Angrily he

addresses Turpin. "Hey sir priest, may God cover you with

shame! You are my relative; you should love me and this is the

tale you come to tell me! It is you who dare ask me on behalf of

the son of the dwarf that I give him homage! His father, Pépin,

was so small that he seemed to roll when he walked. Tell your

Charlemagne that, if he passes through my lands, he will not need

to go up to Aspremont to fight great battles. By the way, you will

not be allowed to return and give him my message." So saying,

Girard took a very sharp knife in his hand and suddenly threw it

at the Archbishop, but Turpin turned away and dodged the blow.

"Girard," said he, "it is therefore the devil who takes away

your reason. You will see your land always go from bad to worse,

old man, who has a passion for murder. When the pope learns of

your action, he will excommunicate you and reject you from holy

Christianity."

"I do not care about your pope! To baptize, to marry, to

confess, I will never appeal to him. I will indeed create a pope

myself, if such is my will. To no man on earth ever, were it for the

cost of an egg, will I pay homage. God alone is my Lord. As for

your king, I will only grant him my love if he bows at my feet."

"Certainly you are completely out of your senses," replies

the Archbishop. "From whom do you want to hold your fief?"

"From Almighty God."

"Well, come and defend him in company with

Charlemagne! Otherwise, you will have a suzerain before long."

Girard almost burst out in anger. "Sir Archbishop, you are

talking madly. Go quickly! Otherwise, by my soul, I will hang you."

"I swear to you by God," replies the archbishop, "that as

soon as he has destroyed the criminal race of the Saracens who

have entered into his legitimate birthright, Charlemagne will

deliver you to a harsh and cruel fate. He will leave you no city to

stay in. He will lock you up in a tower between thick walls and

you will not see the moon or the sun there. Know it well, unhappy

old man without faith and full of disloyalty. There is no creature,

however bad it may be, whom God does not strike down when he

wills."

And, with these words, Turpin returns. He is very doleful

and looks weary, thinking of Girard's refusal. He passes through

valleys, woods, meadows, and fields, and he pulls on his reins

only when he returns to Paris. Once in the city he marvels at the

number of armed men he meets there. There are met the flower

of France and of chivalry. There it is swarming with Bretons,

Angevins, Manceaux, French from Ile de France, Normans,

Picards, Lorrains, Irish, and English. There are so many nations

that a jongleur could never name them all in one of his chansons.

So great is the press that a helmet sells well for two marks of

silver and two spurs for a bezant of gold. And all these armies are

riding in haste towards Laon, where Charlemagne has given

orders to assemble.

CHAPTER 5 - YOUNG KNIGHTS IN THE PALACE OF LAON

In their palace in Laon, the young lords hear horns sounding,

trumpets resounding, drums beating, goshawks crying, coursers

neighing and the noise of armed men riding through the city.

"It is the army of Charlemagne passing by. If only we could

join it!" they say, and, full of ardor, they call the gatekeeper. "Hey!

Noble friend, you who are so generous, let us go to have fun in

the army! To reward you for your good heart, we will make you,

by God, a knight!"

"Silence, vile flatterers," replies the gatekeeper. "I barely

keep this profession. One receives too many bad blows there. Ah,

how I would prefer to sleep quietly here! I received the order to

keep you and for that the archbishop gives me good money. So

you will not get out of here. Cease your vain prayers! Let the

emperor ride and avenge himself on the accursed pagans who

come to dispute his land."

These words inflame the wrath of the young lords, but

they do not say a word until the next day. When the army moved

away from the walls of Laon, their ire redoubled.

Young Roland then summoned them and said to them,

"Here is Charlemagne gone against the vile Saracens. Ah, what

brilliant boredom to remain locked up in this palace! Are we

therefore thieves and murderers for the archbishop to keep us

prisoners like this? Let us talk with the gatekeeper again. Let us

offer him our rich cloaks and, if he refuses to listen to us, we will

strike him with branches from an apple tree, so that he will never

want to be beaten again." And all of them answer: "To that we all

agree!" Hiding sticks under their coats, they go to find the

gatekeeper.

Young Roland, the valiant lord with strong arms, takes the

floor. "Brother-in-law, by God, hello! The king is gone. We would

love you so much if you let us join him! Once we have seen him,

we will return to the castle."

And the gatekeeper replies, "Do not leave this keep! The

Archbishop wants you to stay there. You will come out when

Charles returns. So control your folly!"

And Roland exclaims, "Cursed be you! Take this felon, so

that he no longer resists us."

The young men seize the ugly bastard and beat him

violently. Before everyone has given him two blows, the

gatekeeper has all his bones broken. He is lying here on the

ground lifeless and the noble youths run out.

Roland, Estolt, Haton, and Bérenger passed through the

gates of Laon. They hurry towards the army of Charlemagne.

"Friends," said Roland suddenly, "are we still going to walk on

our legs like peasants? Look at those riders over there. Let us run

after them and, whoever they are, rid them of their mounts." And

the three companions of Roland answer, "To the blessing of God!"

Roland strikes a knight who falls to the ground and stays

there motionless. "Thank you for leaving me your Aragonese

steed!" says Roland and, jumping into the saddle, he rushes on

another knight whom he strikes on the back of the neck and

knocks down on his knees. He in his turn takes the destrier

which he gives to Estolt, and, continuing thus, in a few moments

he provides Haton and Berenger with good and swift horses.

However, the unhorsed, people of Salomon, hastened to

tell their misadventure to the good King of Brittany. "Sire, the

thieves are fleeing yonder. See their green plumes and their

bliauds of ermine fur. Ah, they gave us no time to breathe and

they beat us like you beat donkeys on a bridge."

Salomon exclaims, "After these bandits!" and he rushes

with a thousand of his companions.

We join the young people on the descent of the mountain

of Laon. They had already caught a goshawk that had escaped

from the hands of I forget which baron.

The king recognizes them. "By God," he said, "but it is you,

then, Roland, Estolt, Haton, and Bérenger!" And, approaching

Roland, he hugs him and kisses him in the face. "Hey! How? You

are not in the keep anymore?"

"We killed our felon gatekeeper," said Roland. He explains

the story, and all the lords laugh out loud.

Then Salomon summons four of his noble men. "Guard

them for me," says he, "noble barons."

And these answer, "To the blessing of God!"

Charles rides in haste. His army is now complete, for in

front of Laon, the men he already had, were united Germans and

Teutons, Bavarians and Ardennes. It takes him little time to reach

Rome. Seven kings, fifteen dukes, and a hundred counts

accompany him. Never in the world was there a finer army! In

Rome the pope sings the mass and to Saint Peter the emperor

offers ten gold marks.

May God protect Charlemagne and his family! But what

fierce battles the Christians will have to engage in against the

enormous assemblage of pagans! Below Aspremont, Turks and

Persians, Africans, Moors, Indians, Amoravians, Lutissians, white

and black Saracens are so numerous that no jongleur, either

peasant or courtly, could ever tell you the full story.

Lords, all listen to this proud song, as Charlemagne

ascended to Aspremont and destroyed Aumont and Agolant.

CHAPTER 6 - AT THE COURT OF GIRARD OF FRAITE

However, in Vienne, in his palace which was built centuries ago,

Girard of Fraite gathered his family, Dame Emmeline, his

courteous wife, his four sons Ernaut, Renier, Claron, and Bovon

and all his knights.

"Barons," he said, "you, like me, were amazed that

Charlemagne, who governs France, dared to ask me to fight at his

side. Had it not been for God, who wants him to defend against

the Saracens, I would have placed myself at your head to ask him

the reason for such an outrage. I have raised and protected you

all for your greater good and profit, and now I am beginning to

grow old, for I have long passed my first hundred years. I order

you, when my life is over, to take nothing from Charles of the

fierce visage. His father was a miserable dwarf who robbed

everyone, great and small. And it is I, it seems to me, that

Charlemagne should recognize as his suzerain."

"Sir Girard, what are you saying?" interrupts Lady

Emmeline with a proud face. "The King of France has power over

everyone. You know that this is how God willed and decreed it.

What are you doing here, pitiful duke! Did you not hear that

Agolant, the pagan, with Aumont his son, crossed the sea? They

are leading numerous armies, they kill Christians, and they want

to destroy our faith. Truly you have, in your life, committed so

many crimes, burned so many churches, put so many people to

shame and to death that you are patched all over with mortal

sins. Why do you not go against the Saracens to obtain pardon?

Join Charlemagne with your valiant men." So said Lady Emmeline

with a proud face.

Now, lords, be silent and listen to me well. One should

love and cherish one's wife, one should follow her advice when

she is sage and wise; but if she does not have sufficient reason,

one must frankly disavow her.

"Well," continues Girard, "it would be better to die and no

longer be lord of any land than to go, under the banner of Charles,

to strike an enemy. Let him fight against the Saracens! I will seize

France, so that Charles will never be able to return there."

"Truly," insists Lady Emmeline, "may God curse you! Bad

have you always been and bad you want to finish! By you, so many

noble men and valiant ladies have been tortured and reviled,

driven from their lands and stripped of their goods! It is a marvel

that God still suffers you and does not punish you with a bad

death when you do not want to obey his commands. Girard, frank

paladin, remember how you served God! Did you not kill Duke

Alon and dishonor his two daughters? All your jubilation and all

your joy consisted only in doing evil. You amend yourself of

nothing, you are becoming worse day by day. It has been a hundred

years, Girard, since you took me as your wife, and since then you

have never been weary of mischief. Theft, pillage, arson, these are

the crimes in which for a century you have never ceased to

delight. Girard, call for your men. Fly to the aid of Charlemagne!

Go against the pagans to atone for all your crimes."

Girard hears his wife and his face begins to whiten

somewhat. "Lady Emmeline, why hide it from you? I would gladly

depart, but I would derive neither glory nor profit from it. All the

honor and the gain would be for Charlemagne."

"Certainly," replies Dame Emmeline, "I would not abandon

the enterprise for such a reason. I would gather all my army. I

would arrive in Aspremont in the wake of Charlemagne,

according to my power I would avenge God, then I would come

back via Saint Peter's in Rome where I would be washed clean of

all my sins. Remember that you are old and your flesh is

weakening."

Girard listens to Dame Emmeline. His heart softened, he

can no longer control himself. With great tenderness he grants

what she asks. He begins to sigh for his sins. "Lady Emmeline," he

says, "leave me alone. I would now like to be in accordance with

God." Then Girard orders to have his letters sealed, he sends them

to all the lords of his kingdom. Princes and knights rush to him

from all parts.

When he sees them, he says, "Barons, we must leave. King

Agolant has crossed the sea, his son Aumont, as I have heard told,

wishes to conquer France on top of Charlemagne with an army so

large that it cannot be numbered. If he can defeat Charles in

battle, sooner or later we shall have no chance of escaping the

same fate. Forward then, barons! If God grants that I return, I will

know well to whom and how to demonstrate my love."

Girard orders his sons to arm the knights. Then he turns to

his sweet wife. "Lady Emmeline, I am leaving for holy battle. If

ever I have angered or annoyed you, I beg you, now, to grant me

your forgiveness." And, crying, Girard hugs Dame Emmeline.

Girard walks away. He swears, the old man with his white

beard, that this day will bring bad luck for the Saracens. He rides

non-stop all day, morning and evening. He hastens towards the

army of Charlemagne, which has now left Rome and has been

ordered to go to Aspremont to dispute the Christian land with the

Saracens.

CHAPTER 7 - RICHER MESSENGER OF CHARLEMAGNE TO AGOLANT

Charles rides, our great emperor. Around him are his dukes and

vassals; to guard his banner he has a hundred thousand men. He

raises his hand and in the name of the Lord God he blesses his

army. "Oh God," said Charles, "who with your own hand created

heaven and earth and sea and water and countryside, confuse the

vile and savage race of the Saracens who invade my kingdom!"

Charles is in sight of Aspremont. He orders the army to

stay four days so that everyone gets a good rest. Then he sends

for all his barons. Counts and dukes, peers and princes come

immediately, as well as the pope himself. Everyone is seated

around the emperor.

"Lords," said Charles, "before going further and striking

the Saracens, which one of you will want to carry my message to

the fierce Agolant and at the same time count the number of our

enemies?"

No one answers. After a few moments here is a lord who

decides to get up. He is the good Ogier of Denmark. He unties his

cloak and kneels before Charlemagne. "Fine sir king, you must

have no trouble. In your court I know of no knight who can serve

you better than me. I will go up to Aspremont for you."

"Ogier," said Charles, "withdraw, please. Never speak of

that again, unless I ask you to."

Then rises the seneschal Fagon, the greatest duke, cousin

of Charlemagne. "Sir Emperor, I am your relative and I am your

baron. It is from you that I hold Tours and all of Touraine. I am

the seneschal of your household. It is I who bear your banner. To

whom can you confide if not to me? I will go up to Aspremont for

you and I will enumerate the army of the pagans."

"Fagon," said Charles, "leave this speech. Take your place, I

will not send you there."

Then rises Geoffroy Grise Gonèle, Duke of Paris, the

bravest lord. "Sir Emperor, do not be afraid that the pagans will

steal these lands from us. You know well what I have done for you

in Saxony. I will go to Aspremont if it is your pleasure, to talk with

the Turks and the Arabs."

"Geoffroy," said Charles, "do not show such haste. You will

not go, I tell you no more."

Then rises the good Aubuin, Duke of Beauvais. "Hey! King

of France, I will climb the hill of Aspremont and inquire about the

forces of the Saracens."

"Far be it from you, such an idea," said Pepin's son. "I will

not send up any man of noble lineage who has land to rule, lest

those accursed heathens put him to death. Is there not among

you a poor knight, without land and without an heir, to carry my

message to Agolant, that haughty and proud pagan who would

like to take my empire away from me?"

Then comes the good vassal Richer, nephew of Count

Bérenger, cousin of the good King Desiderius. Before

Charlemagne he kneels. "Sir Emperor, I am a knight, without son

and without fief. If you deign to choose a man of my rank for your

message, I am at your disposal."

"Friend," said Charles, "I am willing to grant you this

honor. If you return safe and sound, I will grant you a magnificent

reward."

Richer remained before Charlemagne. The king hands him

the message which he must deliver to Agolant. But Duke Naimon

approaches the great emperor. "Sire, you have made a bad

decision. Richer is brave, he is full of courage, in your court I

know of no better knight. If these miscreants kill him, I will be in

great mourning."

"Naimon," said Charles, "do not be irritated. If he comes

back, he will be nobly thanked. Let him go to the pagans and

speak to them with reason and force, for they are proud and

treacherous people."

"It weighs heavily on me, Sire," said Naimon. I know

Richer well, I have fed and brought him up in my house. He is

fiercer than a lion, he will not take long to arouse the pagans

against him."

"Sir Naimon," said Richer, "no other than me will go.

Charlemagne granted me the favor. I will go up, if I can, to

Aspremont."

Charlemagne said, "Let Richer go! With the blessing of

God!" and then Richer went back to his tent to arm himself.

CHAPTER 8 - RICHER'S TERRIBLE ADVENTURE

Richer puts on his hauberk, he laces his round helm, and on his

left side he girds his sword. He mounts his horse and takes a

shield on which a lion is painted. He walks away from the tents,

carrying Charlemagne's letter. May God protect him, because he

is running towards a terrible adventure.

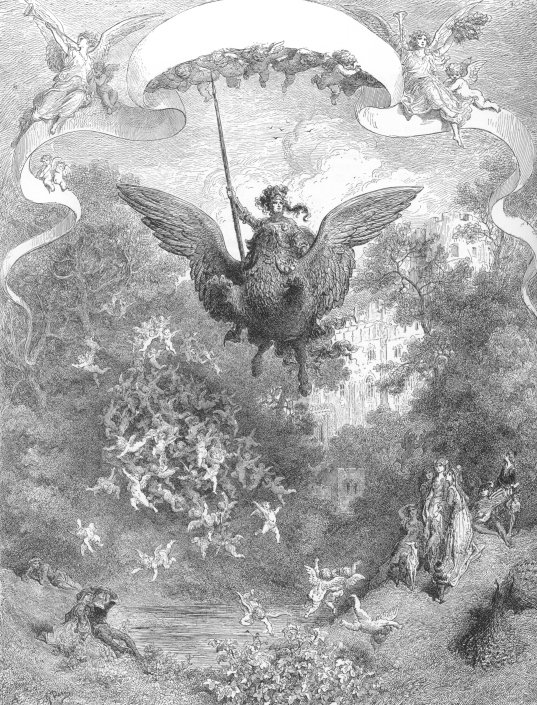

He is approaching Aspremont when suddenly he sees a

griffin, perched on a rock, staring at him with both eyes. The

horrible beast has wings as long as a lance. It measures thirty

feet from the tail to the nape of the neck and three feet from the

beak to the forehead. She is strong enough to carry the load of a

mule. Her eyes are red as burning coals. When it flies, the sound

of its wings can be heard as far away as the range of an arbalest.

She left her little ones at the top of the mountain and she

searches through the vast solitude for food for them.

She flies against Richer at full speed and she violently

strikes his shield with her wings. Neither reins nor stirrups can

hold the knight back. He falls and, before he gets back to his feet,

the accursed griffin seizes his steed. She plunges her claws into its

thigh and with her beak she tears out its liver, lungs, guts and

entrails, with which she flies away to find her young.

Richer gets up, angry and very upset. He draws the sword

he has girded at his side, but the bird is already perched on the

rock overlooking the mountain. Richer is full of ire and fury.

"God!" he exclaims, "How can I reach Aspremont, now that I have

lost my Aragonese horse? If I plunge into this torrent, its

disorderly course will drag me away."

Richer, the good vassal, is overcome with grief when he

sees that he has lost his destrier but he wants to cross the

torrent. He throws himself into the turbulent waters.

Undertaking full of folly! The current carries him along and he

would soon have come to his last hour, if Our Lord had not

provided him with help and succor by placing within his reach a

strong root which was planted on the edge of the torrent.

Grabbing it with all his strength, Richer climbs onto a rock and,

jumping from stone to stone, he regains a narrow path. "Oh God!"

he said, "How dare I return to the Emperor's tent? What will Sir

Naimon say, my lord, who raised and protected me?"

The valiant Richer finds himself below Aspremont. A

swarm of owls, falcons, and merlins had swooped down on the

dead horse. Suddenly an enormous scorpion advances against

Richer. It seizes the noble knight by his heel and tears off the

spur which is on his foot.

Richer feels that he will not be able to resist any longer.

For better or worse, he decides to retrace his steps and he only

stops when he arrives at the tent of Duke Naimon. There he tells

the valiant lord the cruel way in which the birds of Aspremont

slew his Aragonese steed. Naimon listens to him, full of shame

and pain.

"I thought you were a very noble baron. I am very sorry to

have raised you. In you I nursed a vile coward. No, coward, you

never dared to approach Aspremont," he says and he snatches

Charlemagne's message from Richer's hands.

Duke Naimon is prey to a violent wrath. He overwhelms

Richer with sharp reproaches, Richer whom he nourished. Then,

in haste, he arms himself. In a few moments his chamberlains

prepared his good horse Morel for him, with rich coverings they

have armed him, and here is Naimon, the noble and proud vassal,

who mounts his courser with a robust and well-built body. How

many tears his men shed on seeing him depart!

On learning of the departure of the noble baron,

Charlemagne is filled with ire and bitterness. "Lord, here I am

completely robbed. If I lose Naimon, my good and illustrious

vassal, never in this world will I have jubilation in my heart."

CHAPTER 9 - THE WRATH OF DUKE NAIMON

On his robust Morel, Duke Naimon goes to carry Charlemagne's

message to the Saracens. He rides up straight and steep slopes

and the snow falls and covers his horse's neck. Duke Naimon is

white from his hauberk to his saddle.

He passes close to the ravine at the bottom of which the

turbulent waters carried Richer away. Icicles fall on it and

stumble over each other. The torrent is as wide as the range of an

arbalest. To pass it, Duke Naimon finds neither plank nor bridge.

Then, invoking Saint Mary, he throws himself with his courser

into the middle of the torrent. The Almighty protects him and

there he is on the other side. He jumps down from Morel, who is

shaking all over, frozen and torn, and they both rest for a few

moments. Then Duke Naimon gets back on Morel, but he has hardly

advanced a few steps when he finds on his right a ravine as steep

as a cliff which plunges into the sea. "Oh, God!" said Duke

Naimon, "It is not very good to dwell here. If Charles, my lord,

should pass through these places, he will hardly give King

Agolant any fear."

Duke Naimon has climbed the slope of Aspremont and there

are the birds, eagle-owls, vultures, falcons, merlin falcons, eagles,

cat-owls, owls, and huge owls who see him from the top of their

lair. The griffin who had so mistreated Richer descends on him. It

lifts Morel thirty feet off the ground and drops him from that

height. The Duke Naimon was nearly knocked from his saddle.

Duke Naimon is afraid. "Lord Saint Gabriel," he said, "the

royal army will never be able to pass here. Emperor Charlemagne

will never be able to cross these places. What pain, what suffering

he will endure!" Then he draws the sword hanging from his side.

He strikes the griffin with such force that, as God willed in his

goodness, he cuts off the two feet which cling to the horse's neck

and remain suspended near the saddle. The griffin's leg was as

long as a spear, from the heel to the tip of the beak, a stripe of

wine or water would have entered the beast's body.

Naimon spurs his horse. He will show it to Charlemagne.

The valiant Naimon looks on either side, and at the foot of

a rock, he sees the spur of Richer and his steed who was lying on

the sand. "Oh, God!" said Naimon, "By your most holy name, how

wrong was I to blame the noble Richer!" When he reaches the

summit of Aspremont, it is pitch black. The birds fled. The duke

lies under a leafy tree and he lays his sword down beside him. It

is snowing, it is weather that no man in the world can resist. The

duke is severely tried.

Against a rock Naimon shelters Morel and, to protect

himself, he has only the leafy tree. It is windy, it is snowing, the

duke is cold, all his flesh trembles, and all night his teeth strike

against each other like so many hammers. Oh, what a night Duke

Naimon passed! From such a night no noble lord ever escaped.

Duke Naimon will never forget it.

Suddenly, at daybreak, a bear appeared, coming there to

look for her newborn. She had given birth to him in the rock near

which Duke Naimon had stopped. Mouth wide open, she rushes,

furious, on the valiant baron.

"God, protect me!" said the duke, drawing his sword and

awaiting the beast with a firm footing. With a single blow from

his weapon, he cut off the two paws of the bear who, after a vain

effort, fell back. Ah! if you had heard the sound of its howls which

resound all across the mountain!

Suddenly, a bear and a leopard appear. They see the horse,

they want to jump on it, but Naimon draws his finely sharpened

blade. He cut off the leopard's head and the terrified bear fled.

Finally the sun rises again and Naimon descends the slope

of Aspremont. He discovers the pines and the mountains of

Calabria. He sees thousands of barks and boats rocking on the

strait, and around the pavillions which are placed on the shore on

all sides, a swarm of Turks and pagans who go and lead a great

fracas. And bitter are the tears this sight draws from the valiant

Duke's eyes, for he also foresees the cruel sufferings and

mournings which lie in store there for the Christians.

CHAPTER 10 - ENCOUNTER OF DUKE NAIMON AND GORHANT

Through a spy Agolant learned that Charlemagne's army had left

Rome and was advancing towards Calabria. Gorhant, son of Balan,

offers himself to the king of the pagans to serve as his

ambassador to Charlemagne. "Give me," he said to him, "your

white destrier which came from overseas the other day. I will ask

him what he prefers, to let himself be stripped of his kingdom or

to keep it while worshipping Mahomet."

The pagans say, "Sire, give Gorhant your white destrier."

And here the richly caparisoned steed, wearing a silver saddle,

bridle, and spurs of gold, is brought in by Agolant's order.

Gorhant hastens to put on his hauberk, to lace up his

shining helm, and to strap on his sword with a shining gold hilt.

Around his neck he puts his heavy shield bearing three leopards.

Then he climbs up and seizes his gonfanon fixed by three gold

nails to a pole, the top of which is armed with a sharp iron point.

Before leaving, he bids everyone farewell. Addressing the

queen, he said to her, laughing, "I am leaving, lady queen. I

entrust you to Mahomet. I am going to see this Charlemagne who

is said to be so formidable and to meet his famous knights."

"Go on your way," answers the queen. "To my god

Tervagant I commend you, may he protect you! You know our

agreement very well. If you love me, never let it be said or known."

"Lady, I will act according to your command." Gorhant

rides on his horse that is whiter than an apple blossom. It is no

wonder that he has joy and pleasure in his heart. He is rich, bold,

a good chess player, adroit hunter, ingenious and brilliant in

words, hard and proud against the arrogant, humble and merciful

towards the little ones, and generous with his treasures. Well

made in body and of amorous complexion, he has captured the

gaze of the queen.

Suddenly he finds himself face to face with Duke Naimon.

"Handsome sir," said the valiant Duke of Bavaria, "have pity on

your horse. If you continue to walk at such a pace, before you

have reached the top of this peak, your mount will be exhausted."

"Who are you? Have you been baptized?"

"Indeed, Sire, I was. I believe in God, the supreme judge

whom the Jews put on the cross."

"Certainly," said Gorhant, "you hardly conceal yourself

from being a Christian. Are you from France, the good country so

renowned?"

"Yes," said Naimon, "I am from the city of Laon. Our

Emperor sent me to Agolant to ask him why he had settled in his

lands, killed his people, and desolated his kingdom."

"You got yourself into a bad adventure," resumes Gorhant.

"By Mahomet, it is your misfortune that your great emperor sent

you here. I think you will not be returning home in perfect health.

I really want to have your horse. Go get another if you do not want

to continue on foot."

"Sire," said Naimon, "it would be a sin to do so. Let me first

carry my message, then we will resume this dialogue."

"Knight," insists Gorhant, "your black horse pleases me, it

seems to me so fast, so strong, so robust. Dismount at once, you

will ride no further."

Naimon replies, "It would be inappropriate for

Charlemagne's man to go on foot like this. Please, I tell you once

again, wait until I have carried my message to your king Agolant.

Then, in exchange for your white horse, I will give you my black

horse. God confound me, if you do not have my last word there."

Then Gorhant exclaims, "Your horse this instant!

Otherwise, beware of my steel!"

"Never!" replies Naimon.

Gorhant wields his spear; but with his own Duke Naimon

strikes the pagan on the first quarter of his shield, which he splits

and pierces, and he cuts the mesh of his solid hauberk. Gorhant

returns the blow and breaks his iron on Naimon's golden shield,

of which he does not however manage to break the slightest part.

Naimon and Gorhant then draw their swords.

Ah! If you had been there, you would have seen the rivets

of the helmets fly, buckles of the shields loosen, and fragments of

armor fall to the ground!

Suddenly, on the golden circles of Gorhant's helm, Naimon

strikes a blow so furious that the heathen is dazed and he cannot

see a thing. He clings to the saddle of his destrier, which takes off

at a gallop.

Naimon laughs and exclaims, "Where are you going pagan?

Admit it, I have lowered your pride a little."

However, Gorhant remembers the one who greeted him so

nobly in the morning. He sits up on his steed, pulls the reins, and,

sword drawn, he comes back to Naimon. They fight until they are

weary. Finally, they stop and Gorhant says, "Knight, brother, speak

the truth. Are all Christians as brave and valiant as you?"

"Vassal," said Naimon, "I have not tried them all, but there

are certainly many better ones. Stop your questions! We will

begin again, if it pleases you, after we have carried our messages,

I my message to Agolant, and you yours to our great Emperor

Charlemagne."

Finally they agree and Gorhant leads the Frenchman near

Agolant. They cross the ranks of the pagans. In Gorhant's shield

they first see a hole large enough for a hawk to fly through. They

also notice his helmet severed to the visor. They begin to murmur

among themselves, "Truly this foreign lord is neither a knave nor

a coward. If the Christians know how to defend themselves in this

way, we were hardly well advised to come to them and to dispute

their lands."

CHAPTER 11 - DUKE NAIMON SAVED BY BALAN

Duke Naimon is before Agolant. The pagan king addresses

him with pride and wrath. "Who are you? Speak frankly, vassal.

Are you a knight? Do you own land?"

Naimon replies, "I am a man of Charlemagne. It was he

who gave me a knighthood. I am his sergeant and his master

gatekeeper. The other day he gave me a little land, and when I

come back he will give me a wife. Before that I had not a

single denier."

Agolant said, "Saracens and Slavonians, guard this

Christian for me and bring him to me tomorrow morning. I will

have all his limbs cut off. In spite of Charlemagne, I will have him

quartered."

"Sire," said Naimon, "do not be in too much of a hurry. A

noble-hearted king does not recognize the right to act thus

towards a messenger. The emperor, who sends me to these places,

wants me to ask you yourself why you committed the sin of

coming to these places, of putting his people to death and his

kingdom in ruins. Do you want to deprive him of his legitimate

inheritance?"

"Yes," said Agolant. It cannot go otherwise. If, before being

baptized, he had come to me asking for mercy, I could have

agreed with him. Let him bow before me and deliver his empire

into my hands, if he does not want to be disinherited while alive

and then perish in a new kind of death!"

"Sire," said Naimon, "you will have to wait a long time

before obtaining such a renunciation from our great Emperor

Charlemagne."

As Duke Naimon pronounces these proud words in a loud

and firm voice, here comes a pagan who whispers in his ear.

"Knight, give me your sword. If I perceive that anyone here wants

your death, I will help you like a father helps his child. I have not

forgotten what you did for me when I was in France. With all my

power I will protect you. I am Balan." Duke Naimon heard him

and thanked him very much.

Duke Naimon stands before the King. Balan takes off his

helm and his hauberk. He replaces them with a rich ermine and a

cloak of dazzling silk.

"Agolant," said Duke Naimon, "here is what I ask of you

through Charlemagne. Will you flee from these places or will you

advance further? France is so big and so vast that a trotting mule

would take more than three months to traverse it. If you wish to

conquer it, name the place, the location, and the hour of the

battle."

King Agolant calls Sorbrin, one of his advisers who had

lived for an entire year at the court of Charlemagne. There he

spied on our great Emperor, who, not on his guard, seated him at

his table. "Do you know," said he, "this accursed messenger?"

"Sire," answers Sorbrin, "by our God Apolin! I know him,

as I know all of Charles's men, Droon the Poitevin, and King

Salomon and King Thiorin, Hoel of Nantes and Geoffroy of Anjou,

Duke Anquetin of Normandy, Baldwin of Beauvais, Archbishop

Turpin, Cahoer, the king of the English, and Girard of Fraite, who

harbors a mortal hatred towards Charlemagne. Yes, I know this

lord who is there before you. He is not, as he told you, a poor

knight, a wretched gatekeeper without money or mail to whom

Charlemagne would have given a piece of land not long ago. By

Mahomet who can judge us all! He is the wisest and most valiant

of Charlemagne's men, the one whom the Emperor of France

loves and cherishes above all. If you want to fill the heart of

Charlemagne with wrath, have the limbs cut off of this man who

is none other than Naimon, the illustrious Duke of Bavaria."

Balan touches Sorbrin's shoulder and says to him in a low

voice, "By Mahomet, shut up, son of a whore! If ever I hold you

between my fists, I will beat you well in such a manner that you

will never be able to cause harm to a noble man again."

Then addressing Agolant, "Sire, are you going to believe a

vile flatterer? I know Duke Naimon of Bavaria well. There is no

finer knight in France and this man is not worth a denier. Do

you believe that Charlemagne with the proud face would have

sent you his great counselor, or just one of his servants? Certainly

not. He did not send you a sergeant or a valet. As for this Sorbrin,

if you hand him over to me, I will immediately plunge him into

this water until he drowns. And you, noble sir, listen to me. Do

not believe flatterers and act like a true king. Follow the example

of the princes who have gone before you. When a messenger

speaks to you, hear him in silence and without fear and, if he

speaks arrogant and outrageous words to you, limit yourself to

laughing at them. This is how Charlemagne acted the other day

when faced with my threats."

Agolant then said, "As you please, Balan. Take this

messenger, harbor him, and if he desires sendal, orphrey, mare,

mule, or steed, grant his request. Do to him as Charlemagne once

did to you."

"Fine sir," answers Balan, "let it be as you please!"

"Messenger, brother," then said Agolant, "you can go and

tell Charlemagne that the battle will take place within three days

in the meadows of Aspremont. Tell him this again and conceal

none of my words from him. Never, since he was armed as a

knight, since he had his sword girded on his left side, has he seen

such a battle, nor such a quantity of pagans. But, if he wants to

renounce his Christian name and adore Mahomet, I will, I believe,

still have pity on him."

"Sire," said Naimon, "I listened to you carefully and I can

assure you that such never was and never will be his will." With

that, Naimon prepares to depart. He asks for his leave and Balan

leads him to his tent. He provides the Duke of Bavaria with fine

silk costumes brocaded with gold, then both go to the table.

Naimon sits next to Balan. A crowned king, who is none other

than Gorhant, serves him and wine is poured out into golden

cups for him.

Balan leans close to Naimon's ear. "Fair Sir Duke, welcome!

You have done me great honor in your kingdom. The same will I

do towards you during all the course of my life. For my part, greet

Charles and give him my friendship. If this combat could be

avoided, I would be baptized immediately." Gently, Duke Naimon

thanks the noble Balan.

CHAPTER 12 - THE LOVE OF A PAGAN QUEEN

Meanwhile, Queen Aufélise, wife of Agolant, learned what had

happened and what tone the Frenchman had used with regard to

Agolant. She commands Balan to come and introduce the

messenger of Charlemagne to her.

When she sees Balan and Duke Naimon entering her tent,

she rises from her seat. With her right hand she suddenly seizes

the right hand of the valiant Frenchman and with her left hand

she forcefully grabs his baldric adorned with precious stones,

then she makes Naimon sit down and she seats herself at his side.

She never tires of admiring the beauty of the bold knight,

his clear face, his large eyes full of fire, his tanned complexion,

the bruises left on his forehead by the heavy, clumsy helm. She

immediately felt herself burning with love and to herself she said,

"Mahomet, if by your power you put me with him in a richly

curtained bed, you would allow me to enjoy sexual pleasure

which would be well worth a kingdom. Agolant never would be

spoken of, for this Christian is full of youth, grace and vigor while

Agolant is all decrepit in old age."

Aufélise calls Naimon in a soft and tender voice.

"Frenchman," she whispers, "in the name of the Christian faith,

tell me, do you have a wife in your kingdom? And are all

Christians as beautiful in appearance as you?"

"Lady, I have not tried it. There are a great many more

than me. You ask if I am married. Oh no, I had never thought of it!

For in the service of my lord I dedicate myself entirely. And if one

day I marry a woman, it will be Charlemagne who chooses her

for me." These words fill the queen's heart with jubilation.

Quietly, secretly, she takes the baron's hand, then she puts a ring

on his finger.

"Lord," she said, "with this ring of fine gold I give you my

friendship. Keep it, for it has great virtues. If you lose it, you will

never find another like it. As long as you wear it on your finger,

you cannot be bewitched, poisoned by venomous herbs, nor

dispossessed of a single denier of the immense riches which

you have amassed, nor defeated in battle, nor condemned in

justice, nor lose your way. If I entrust it with you, it is so that

when you return to your country I can quietly brag that secretly I

have a warrior in the Christian world, and if I were to be loved by

you, all my life it would be a very dear joy to me."

"Lady," said Naimon, "you have done me so much honor

that responding is entirely impossible for me." He asks for her

leave and she grants it to him. Seeing him depart, she sighs from

her heart and tears flow down her face. And Duke Naimon leaves

her, deeply moved and deeply shaken.

Balan retires with Duke Naimon. To the valiant knight he

offers goblets of fine gold and rich cloaks of silk, vessels of

gold and horses and deniers, but Duke Naimon refuses all these

presents. So Balan brings in his good horse. It is a courser whiter

than snow and crystal, he has a fine head and a splendid rump, its

golden bit is wrought with enamel, its saddle is of pure gold, and

a rich silk covering protects its body. And Balan said, "Behold this

horse, noble duke. To run over hill and dale it is faster and more

resistant than any beast in the world, and no mortal should ride it

unless he is a vassal of the bravest and boldest. Now, then, take

this good courser to your king, and tell him as you give it to him

that I promise to make myself a Christian once our strife has ended,

but, as long as the rumor and the dread of the fighting lasts, I

will not abandon the Saracen belief."

"By Mahomet!" say the pagans watching the Frenchman

cross their groups, "if all the Christians are so proud in

appearance, we will not bring back to Africa either a mule or a

palfrey."

Balan escorts Naimon back. When both are in sight of

Charlemagne's army, Naimon said, "Balan, come to us when it

pleases you. The pope will give you baptism."

"Thus would I have already acted," replies Balan, "but

Agolant, my lord, raised me and knighted me. It would be a crime

to fail him now, and I do not want any man to reproach me later.

And yet I know only too well how the fight will end and that we

will be defeated. Give greetings from me to Charlemagne and to

all the lords of France!"

Naimon gives the Saracen a cross which the Pope had

given him. Balan takes it and bows. As long as he has it, he will

be safe from death. Naimon also bows and leaves, and he does not

stop until he has joined Charlemagne in his master pavilion.

CHAPTER 13 - DEFEAT OF AUMONT AND THE FOUR PAGAN GODS

The Emperor thanks God for returning his noble messenger to

him. As he helped him down from his courser, he said to him,

"Naimon, are you safe and sound and intact?"

"Yes, Sire, I only got in trouble when climbing Aspremont.

Ah, how wrong we were to blame Richer! On the sand I found his

spur and the bones of his horse." And he recounts his terrible

adventure with the winged beast. He pulls from his shoe the claw

which he gives to Charlemagne. With surprise and terror he looks

at the remains and he shows it to all the lords who marvel at it.

"Take this magnificent white horse," adds Naimon. "It is

Balan who offers it to you, Balan who is in haste to become a

Christian! Ride, king! What are you waiting for? The army of the

pagans is numerous, certainly, but among the Saracens the price

of provisions is always increasing. A simple glove sells for a mark

of silver, good mules and noble steeds die of hunger, it is on their

flesh that the race of the unbelievers feeds, and for those who are

hungry, what is their courage worth? Ride, king! Aumont guards a

tower built by Agolant with a hundred thousand men. Balan

showed me a road which will lead your army straight to this

tower. You will not need to climb this arduous and high mountain

which seems attached to the clouds. Leave at once with your

household and your people and you will find enough white silver

and red gold to change your poorest relatives into rich men."

"Many thanks, noble duke. But, tell me, what is this ring

that I see shining on your finger?"

"Sire, a talisman entrusted to me by Queen Aufélise, wife

of Agolant."

Charlemagne smiles for a moment, then he calls his

warriors and the pope himself. "In the name of God who turned

water into wine," he said in a loud and firm voice, "tomorrow at

dawn you will set out. Let the sixty thousand men of my vanguard

go straight for the tower of Agolant. I will follow them with a

hundred thousand other men, all devoted to my person. Ten

thousand men will hold my right, without losing sight of me.

Carts full of provisions will accompany us, led by my squires and

escorted by my servants."

All respond, "Have the blessing of God!"

The next day, at dawn, how many horns you would have

heard blaring! How many counts, dukes, and princes you would have

seen riding with their scintillating arms! How many hauberks!

How many helms! What a forest of lances and banners all shining

with pure gold!

Through mountains and valleys rides the great army of

Charlemagne. It only stops half a day from the tower erected by

Agolant. But there everything is in ruins, everything has been

burned, destroyed, devastated by the Saracens. At this sight,

Charlemagne begins to cry.

The armies of Charlemagne, the noble justiciar, have set up

camp. Night is falling. Twelve counts with thirty thousand valiant

iron-clad warriors march towards the tower of Agolant. They

hear noise. Beneath the olive trees, shields around their necks,

spears in hand, they lay in ambush. They keep quiet and silent,

arranged in good order, ready for any event.

Suddenly a thick dust cloud rises close to them. It is

raised by a hundred thousand pagans who return, loaded with

provisions plundered in the towns, the villages, and the hamlets

which they had stripped and burned, after having cut off the

heads of many Christian nobles, the limbs of many little children,

and the breasts of many poor women. In front of their horses,

they push men, children, and more than three hundred maidens,

daughters of knights, tied in pairs like bloodhounds.

At the head of the pagans rides Aumont, the robust and

strong limbed Saracen. And in front of Aumont parade the four

gods of the pagans: Mahomet, Tervagant, Apolin, and Jupiter, each

carried on a pedestal. Their sides are gold, their mouths gape,

they look like four cursed devils.

And the pagans, laden with meat, bread, and wheat, dance,

frolic, and beat their drums. They mock the unfortunate

prisoners who call out with all their voices, "Charlemagne!

Charlemagne!" They reproach Aumont for not having destroyed

the Monastery of Saint Peter and for not having had himself

crowned in Rome.

Aumont promises to take them soon to France where they

will have goods, riches, and beautiful ladies in abundance, and he

shouts, with a sneer, to the poor Christian prisoners, "You see

how your Charlemagne, your great emperor, is coming! Do you

not know that he fled out of fear a long time ago? In a short time,

I will be master and king of France, and I will go to Rome to be

crowned."

Our thirty thousand knights perceive these words clearly.

It is more than they can bear. At the summons of Huon of Mans,

they all set off with fury, bows drawn, banners fluttering in the

wind. "By Mahomet," said Aumont, "that is good news. Is it my

uncle Moïsan, or King Esperrant, or King Boïdant who is coming?"

But his standard bearer, Hector, the king of Val Penée,

answers him, "It is the vanguard of Charlemagne. Sound your

Olifant, valiant Aumont. Gather your people. We will soon have

combat and battle."

"Truly," answers Aumont, "I would never think of deigning

to raise my Olifant to my mouth for such people. Our race would

be too dishonored!"

Aumont is proud, strong, and powerful. If he had believed

in Our Lord God, there would never have been a better knight in

the saddle. He sees the counts and the knights going up the hill.

He notices that there are not many of them.

"Truly," he said, "Mahomet cherishes me. He gives me